MEET THE CATS

An important element of research like the Urban Caracal Project is using charismatic focal species as conduits for the general public and residents local to the study area to connect with backyard biodiversity. Getting to know the individuals in a study is a great way to do this!

HERMES (Caracal #33, TMC33)

Urban caracal Hermes was quite the project mascot and he had an interesting life story for his short time on this Earth! So we thought we’d put him front-and-center to our Meet the Cats!

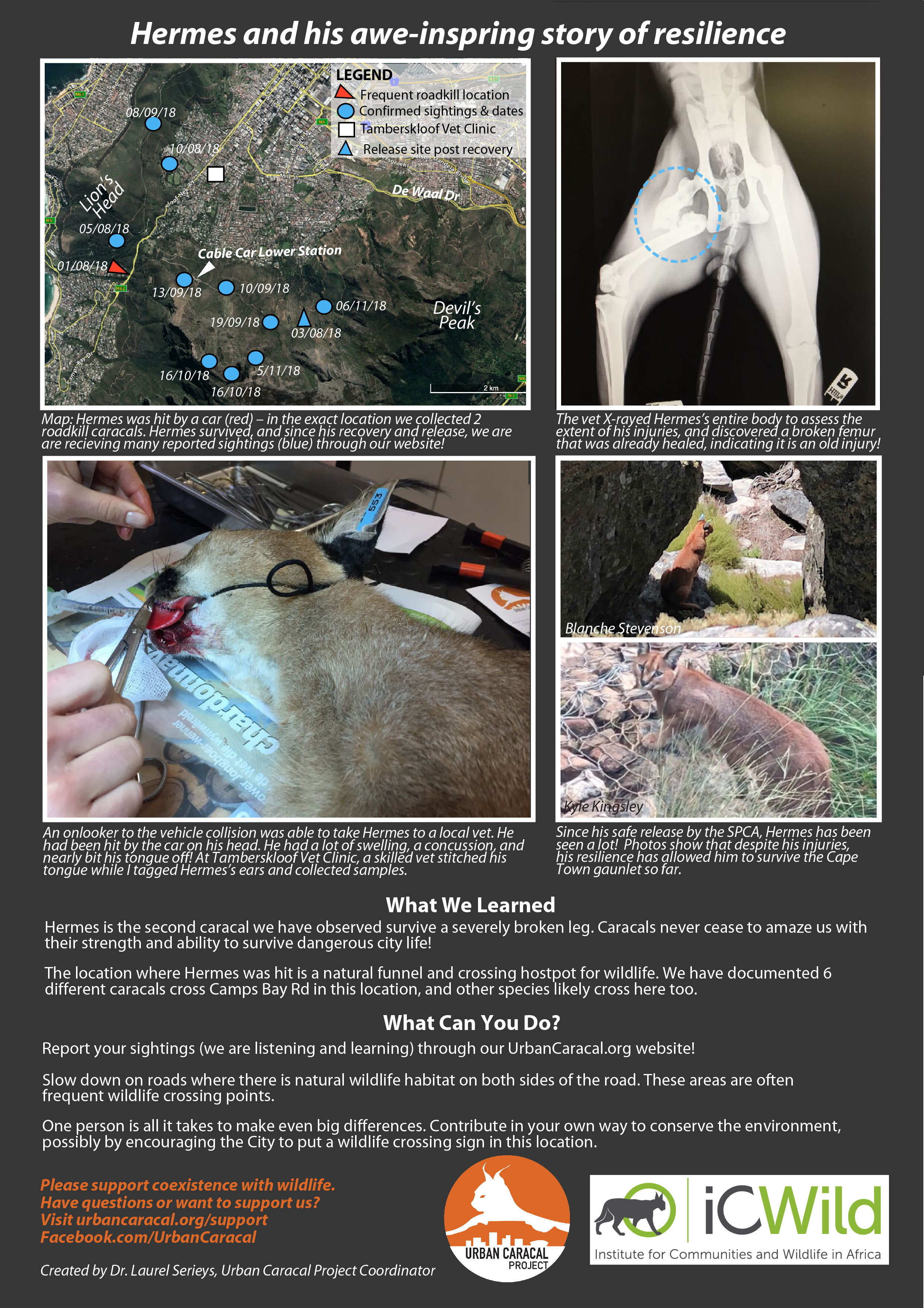

We first met him in 2018 when he was hit by a car on Camp's Bay Drive, in the same spot where at least 2 other caracals have been hit by cars and died. But Hermes survived, though almost bit his tongue off and it was quickly sewn back on at Tamboerskloof Veterinary Practice! While at the vet, we performed X Rays, only to discover he'd clearly been hit by a car before, severely breaking his hind leg But he healed after that incident too, although his right hind leg is a little shorter than his left now! But you wouldn't know it based on the way he struts his stuff for many hikers and joggers on Pipe Track and Tafelberg Road!

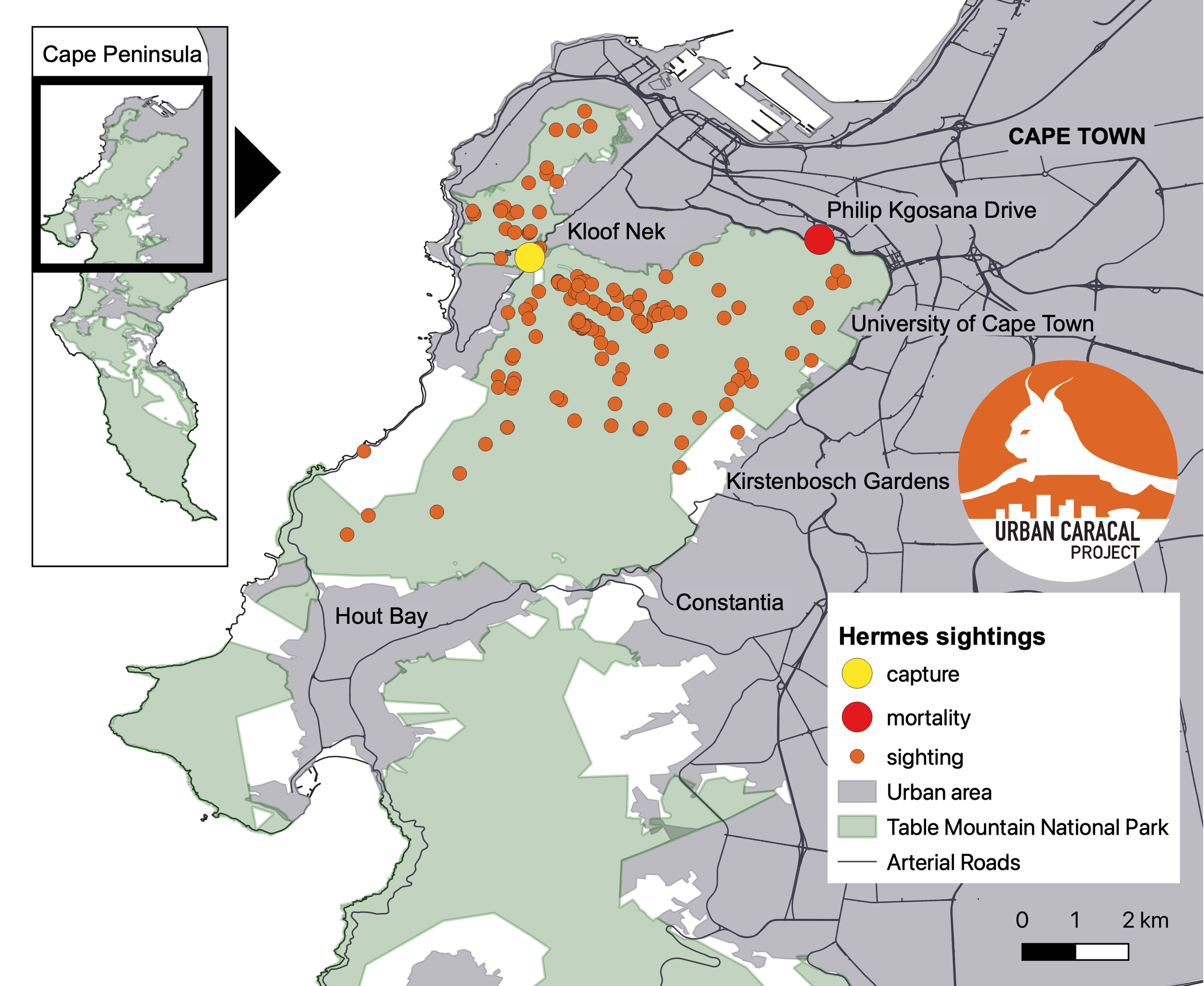

Sadly in May 2023, Hermes was fatally hit by a car on Philip Kgosana Drive (see red dot on the map). As a favourite mountain mascot, the outpouring of sadness and love for him was incredible - many news articles announced it and the project retrieved hundreds of comments and reactions. This was a real testament to the care that Cape Townians have for wildlife staking out a life on the urban edge.

When we met him in 2018, he was between 1-2 years old, so at the time of his death he was around 5 - 6 years old. That's actually "old" for an urban caracal... most of the caracals we find dead are only 2 years old, although their typical lifespan in areas without humans would be around 10 years! Hermes was frequently sighted, as he was easily distinguishable by his light blue and green ear tags.

During non-lockdown conditions, we used to get about 1 sighting report/week for Hermes, although surely he was seen even more! The map shows all the sightings that were reported to us. He was obviously habituated and doesn't mind being seen, but that doesn't mean he was a threat. He grew up in an area with a lot of humans, so for the average hiker that doesn't pose any threat, he didn't mind letting people admire his beauty.

LADUMA (Caracal #01, TMC01)

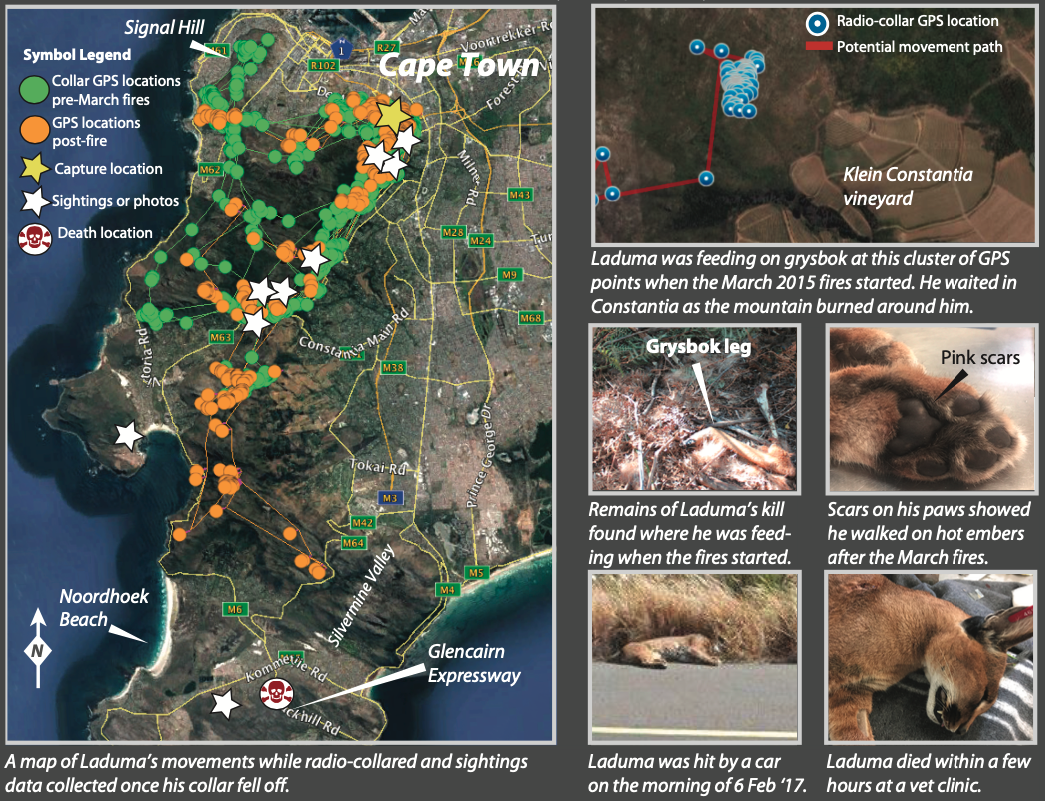

Table Mountain Caracal #01 (TMC01), aka 'Laduma' (Zulu = “it thunders”), was the first caracal that was humanely captured and GPS-collared as part of the Urban Caracal Project. We caught him on November 19, 2014 at the northern section of Table Mountain, after only 10 days of trapping (which was quite impressive given that it was project coordinator Laurel Serieys’s first caracal and first time working in Table Mountain)! As you might imagine, catching Laduma made us all feel like this whole Urban Caracal Project might just work!

Laduma was a healthy, adult male that at 3 years of age, weighed 13.1 kg. He had slight scarring on his face, suggesting that he has "been around the block!" But otherwise, his coat was beautiful and he appeared to be in great body condition. He was fitted with a GPS-enabled radio-collar and we tracked his movements for 162 days, and collected 2,242 GPS points! Much to our surprise, despite a relatively short period of data collection (compared to other carnivore studies), he used a massive area spanning at least 67 square km, moving regularly from Orangekloof , Front Table, Signal Hill, Newlands Forest, Rhodes Memorial, and west to above Camps Bay! And much to our surprised, about one week before the March 2015 fires, he ventured into Constantia. Surprisingly, he stayed in the Constantia area even as the fires raged, possibly "hunkered down" to avoid the flames and heat, leaving the area to head back towards Back Table area only a week after the fire. But something we observed that we had no idea would be something we would see time and time again is that, after the fires calmed and the ground cooled off a bit, Laduma went all the way south to Noordhoek while he explored the areas that had just burned. It turns out that caracals like to visit newly burned areas, probably in search of wildlife that come to feed on the fresh shoots that emerge after a fire. We were lucky that we were able to learn how caracals survive in an environment with frequent fires.

After tracking him for just over 5 months, we learned some interesting things about Laduma, like that he ate a little of everything– we observed him hunt and eat a vlei rat, we found a squirrel tail that remained from an evening snack, we found a pile of feathers from an egret in a ravine that he’d spent time feeding and resting in, and we found a grysbok skull at a kill site in Constantia. He also had a much larger home range than we’d expected, and that he was curious about recently burned areas. But we continued to learn about Laduma even after we “lost contact” with him. We had an interesting sighting reported in Hout Bay, a place we’d never observed him. On February 2, 2017, he was hit by a car on Glencairn Expressway, also an area further south than we’d ever observed him to go! We were able to collect a tooth to have a lab accurately assess his age, and we found out he was 7 years old. We also tested him for exposure to rat poisons and we found he was exposed to 4 different anticoagulant rat poison compounds, meaning that he likely experienced chronic exposure to these poisons!

SAVANNAH (Caracal #02, TMC02)

Savannah at the time of her humane capture in the Front Table area.

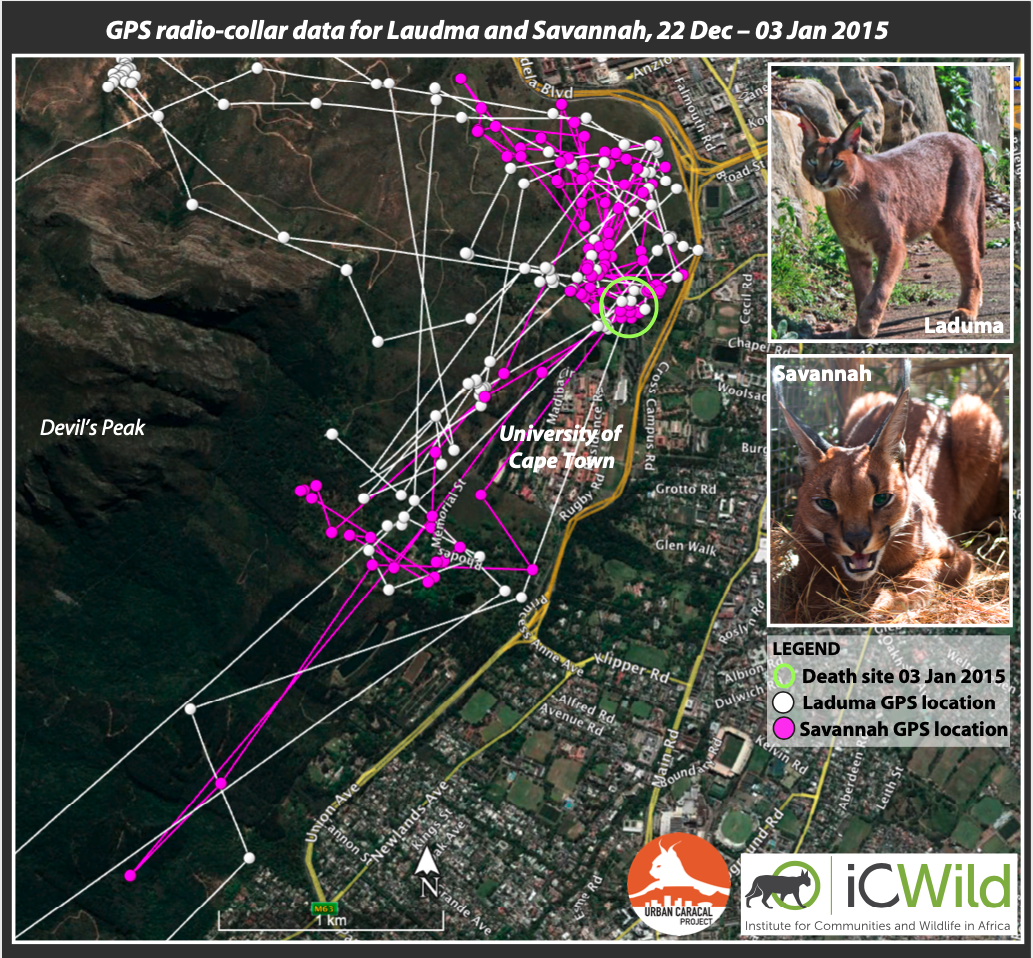

'Savannah,' or TMC#02, was a juvenile (1-year old) female caracal GPS-collared in December 2014 near the King's Blockhouse on the front slopes of Table Mountain. Despite being very young, she already weighed 8.1 kg. We monitored her for only 2 weeks, at which time she was found dead not far from where we initially captured her. During such a short monitoring period, it is impossible to know the full range of her movements. She largely used Rhodes Memorial and the Antelope Paddocks just north of University of Cape Town.

When we found her body, it was in an advanced state of decomposition and appeared to have been scavenged. But we found it very interesting that Laduma, the adult male we’d collared several weeks earlier, overlapped in locations with her. We assumed that he was just curious or investigating a potentially “sick” Savannah. But as it turned out, we conducted as detailed an autopsy as we could and discovered bite marks on her neck! And the bite marks looked exactly the size of an adult caracal! Savannah was actually killed by Laduma, which we have since learned, is not necessarily uncommon in Table Mountain’s caracals. We have now documented 3 instances of one caracal killing another, and in 2 of the 3 cases, the dead caracal was also eaten and cached, just like a caracal would. We were later able to generate genetic profiles for Laduma and Savannah, and it turns out that Laduma was most likely Savannah’s father! In Table Mountain, it is likely that the competition for space drives caracals to fight over resources. In the end, Savannah taught us yet very unexpected facts about the life of urban caracals.

A map showing Savannah’s 3-hour movements, and where she and Laduma crossed paths.

FIRE LILY (Caracal #03, TMC03)

Fire Lily at the time of her capture in Noordhoek.

Fire Lily was the first caracal captured after the March 2015 fires that burned more than 15% of Table Mountain National Park. She was captured on March 27, 2015 near the Noordhoek wetlands area. She was an older female (exact age cannot be determined without pulling a tooth) based on facial scarring, evidence that she’d reproduced, and her pinkish nose (when young, their noses are very dark!). Her name was chosen as a symbol of hope and rejuvenation post-fire, and as an older cat clearly withstanding the challenges of living in fragmented habitat stressed by human-development.

She weighed 7.8 kg, and had a lower body condition than we observed for Laduma or Savannah. This may be related to her age, or that she has clearly been reproductive, having at least one litter of kittens, but likely more! The area she used while GPS-collared exclusively encompassed the Noordhoek wetlands (approximately 9.8 square km), and we have GPS locations for her in tidal pools on the beach! There we discovered that she hunts shorebirds on the Noordhoek beach.

Fire Lily is no longer GPS-collared and we are unsure whether she is still alive. However, she was quite the inspiration to many post-fire, so much so that she has a wine named after her! We suspected some of the caracals that we also caught in the Noordhoek wetlands (TMC05, TMC11, TMC21 and TMC22) could be her offspring, but genetic testing revealed that only TMC05 was Fire Lily’s kitten.

RATEL (Caracal #04, TMC04)

Caught on March 30, 2015, this large adult male, weighing 12.4kg was captured in the Orangekloof area. It was a testament of the will....traps were in that area for months(!) with not a single cat even walking by our traps. We have learned that in some areas, caracal densities are particularly low, and you may not see a caracal in an area for weeks at a time. At the moment, much to our surprise, Orangekloof, despite reports of frequent caracal sightings, seems to be one of those areas. However, in the morning, at 8:30am we captured Ratel. He was one feisty cat, and given his fierceness, we felt Ratel (meaning 'honey badger' in Afrikaans) a very fitting name.

Ratel was radio-collared for 132 days with 1,682 GPS locations collected on his movements. He ranged from Front Table all the way to Kalk Bay, showing once again how far these adult males can move! His range overlapped with Laduma and Oryx's range, which could be unusual for dominant adult solitary male wild cats, but too little is known about these caracals in the urban system.

KATJIE (Caracal #05, TMC05)

Katjie was caught in the Noordhoek wetlands, in the same trap Fire Lily was captured. We initially suspected that Katjie (meaning 'kitten' in Afrikaans) was Fire Lily's offspring and confirmed this to be the case via genetic tools. She was estimated to be approximately 5 months old when captured and weighed 3.5kg. Katjie's story is a sad one. We actually discovered her dead in our trap, but with no evidence of disturbance within the trap itself. Because we checked traps a minimum of four times daily, she was not in the trap for too long, and so it was as if she went into the trap to die. This is the only trap mortality Dr. Laurel Serieys has ever experienced, after years of personally trapping more than 120 wild cat individuals. We were fortunate to be able to perform a necropsy on her shortly after her death with the assistance of two vets, and cause of death was suspected complications associated with rat poisons exposure. Interestingly, the following year, we recovered the body of another young caracal, also in the Noordhoek wetlands. We genetically confirmed this individual was Katjie’s sibling, and Fire Lily’s offspring. Although the body of that caracal was too decomposed to determine cause of death, it died in a bush near Lake Michele, suggesting either disease or pesticide exposure the responsible agent.

Rat poison exposure is a common problem in carnivores in other parts of the world (see infographic). We recommend, instead, taking prophylactic measures: seal holes in homes where rodents can enter, do NOT feed and water birds or other wildlife as this will attract rodents, remove thick vegetation around your homes where rodents may find shelter, and if necessary, use mechanical methods such as snap traps to control rodents found in the home. For more information about these poisons, see Dr. Serieys's website featuring some of the work she did prior to the Urban Caracal Project (http://www.urbancarnivores.com/poisons/).

ORYX (Caracal #06, TMC06)

Oryx as he was being released, post-capture and radiocollaring.

Caught on April 14, 2015, this large adult male, weighing 13.0 kg was captured in the Orangekloof area. Like for Ratel, it was a testament of the will....traps were in that area for months waiting for this big boy to walk by! He was also extremely feisty- more so than any other cat so far. In fact, most caracals are far more agitated in traps than other species Dr. Serieys has observed, after more than 10 years of humane trapping of carnivores for research purposes. Each species seems to have their own personality, and Oryx attests to a special personality quality that caracals have.

Oryx's movement range overlapped extensively with both Ratel's and Laduma's ranges, which is fascinating and exciting for us to document! As presumably solitary, territorial species, we'd expect that such large, apparently dominant, male caracals would exclude each other from their territories. But given the limited space available for caracals across the Cape Peninsula (roughly 320 sq.km. of wildlife habitat), it’s likely that males with large territories are forced to overlap one another. Like Laduma and like Ratel, so far, this older male caracal uses the areas north of Hout Bay Road (from Back to Front Table). Interestingly as well, we have observed Oryx to be in close proximity for periods of days to both Ratel and Laduma, even when Ratel was spotted in Orangekloof with what we think was likely a female caracal (she was not radio-collared). Because so little is known about caracals in general, we are unsure the significance of these observations, but very cool data- and potentially, we are observing the effects of isolation by urbanization resulting in increased overlap in the territories of males! Oryx was radio-collared for just 81 days unfortunately, but nearly 700 GPS locations were collected for him. As of early 2020, he was spotted in Hout Bay and recognizable by his ear tags!

WEST (Caracal #07, TMC07)

A photo captured of West before he was captured, shown here having hunted, and captured, a guinea fowl for dinner! Photo credit: City of Cape Town

West was our first young male radio-collared. He was captured on April 17, 2015 in Westlake. He was an estimated 1-2 years old individual and weighed 8.0kg at the time of capture. His weight alone suggests that he was not full grown, but he was also smaller in size in comparison to adult males Laduma (13.1 kg), Ratel (12.9 kg), and Oryx (13.0 kg). In order to radio-collar West, we partnered with the City of Cape Town who we've been lucky have shown great interest and excitement for the Urban Caracal Project! At the Westlake Conservation Office, city staff were aware that at least one caracal uses the property and so they allowed us to set a trap in the area. After a few weeks of frustrated waiting, we finally captured West in the afternoon, indicating that West was moving through this highly visible area even during the day...unseen!

A photo of West as he walks away from his capture site.

West was radio-collared for 100 days, during which time 1,339 GPS locations were collected. He primarily remained near Steenberg area and the Westlake Conservation Office, but on occasion he has ventured into more developed areas in Constantia, possibly searching for an unoccupied territory to establish for himself.

JASPER (Caracal #08, TMC08)

Jasper being released after his capture in April.

Jasper was captured on April 30, 2015 in the Front Table area near the Antelope Paddocks. The Cape Town caracals really seem to love that area! It is very open and grassy, and we believe that they have strong preference for the area because there is a lot of rodent activity in the grass!

Jasper was recaptured a couple weeks after his initial capture.

He was another one of our young males between the age of 1–2 years old. We were very excited to catch such a young male because he was just old enough to radio-collar, though we did have to line his collar with white foam (visible in the first photo) to make it fit just right. At this age, wild cats are approaching 'dispersal' age- meaning an age that they are searching for their own unoccupied territory to establish. Therefore they may be bolder in entering urban areas during this search. They may also proactively avoid encounters with older males which can also be exhibited in their movement patterns. We are aware of at least three other adult males that use the area he was captured, and seems to prefer (Laduma, Ratel, and Oryx), and so with Jasper's data, we have the opportunity to learn more about how young males use the landscape in the face of being regularly confronted by older 'dominant' males.

Jasper takes off after being released after his second capture!

Jasper was hit by a car on the M3 on July 17. He was radio-collared only 79 days, but during that time, we collected 1,294 GPS locations for him. He crossed the M3, a major road that borders Table Mountain National Park, with great frequency, but this is ultimately what led to his death. His death is discussed in a blog written by Dr. Laurel Serieys (Project Coordinator), and his story was featured in multiple news outlets, including Africa Geographic.

MARINE (Caracal #09, TMC09)

Marine proving just how tough she is with a snarl when she "met" Dr. Serieys.

Females have been rarer catches in Table Mountain National Park but on May 5, 2015, we were thrilled to capture our third adult female! She was a quite a cool catch with a bit of backstory. Three males are known to use Orangekloof, and so we just knew there had to be some sort of "hot mama" of a female there luring those males into the area. So we went on a mission to catch this elusive female. Without knowing exactly what areas she was using, and where we'd most likely be able to capture her, we relied on maps of the movements of our males Laduma, Ratel, and Oryx, assuming they would prefer the areas where they were likely to encounter her! She is the largest female we've seen and weighed almost 9kg!

After radio-collaring her, we observed her to use Orangekloof, but also to cross Hout Bay road and move all the way to Steenberg! In September, her radio-collar ran out of batteries and despite efforts to recapture her, we were unable to do so. We captured a photo of her on a remote camera in the Constantia area and saw that she was pregnant, so we were especially disappointed to not be able to collect data on her while she tended her kittens. In October, she was hit by a car in Tokai. We confirmed that she was lactating, and thus was tending kittens that died as a result of her death. This is just one of the unfortunate realities for these cats in the human-dominated environment. And in Marine's case, her death had a disproportionate impact on the population because her kittens also died as a result.

ATTICUS (Caracal #10, TMC10)

Atticus was captured during the evening on July 26, 2015 in the Noordhoek wetlands area, making him the 3rd cat we caught in the same trap site! Weighing 11.1kg, Atticus was one of our larger male caracals. Living in the wetlands, we found a lot of ticks on him, but otherwise, he looked to be in great condition. Interestingly, he had pink scarring on his paws, suggesting that he may have burned his feet during the March fires. He was no longer radio-collared have observed him to use recently burned areas in Silvermine and Noordhoek. His movements after he was radio-collared were featured in an infographic. Combined with the evidence of scarring on his paws, it suggests that he was near where the fires took place, and may have burnt his paws on hot embers before the ground cooled off post-fire. In total, Atticus was radio-collared for 164 days, and we discovered that he had quite a penchant for preying in high cliffy areas on dassies!

BERG WIND (Caracal #11, TMC11)

Berg Wind was captured on August 7, 2015 in the Noordhoek area. He is a younger male estimated to be 2-3 years old because he at 7.5 kg, he weighs considerably less than our larger males.

Similar to West (TMC07) and Jasper (TMC08), Berg Wind was likely near ‘dispersal' age, during which time he would be searching for his own unoccupied territory to establish. We suspect he was Fire Lily's (TMC03) offspring, though only genetic testing (under way) will confirm this potential relationship. But interestingly, he spent a lot of time near Fire Lily, although he did venture out of the wetlands as well.

Berg Wind found dead near a reservoir in Noordhoek.

We were eager to learn more about how Fire Lily, Berg Wind, and Atticus share the Noordhoek wetlands, but on October 4, 2015, after 55 days radio-collared, Berg Wind was found dead in the Kommetjie area near a reservoir. The cause of death is unknown, but interestingly, he was very emaciated and lost roughly 43% of his body weight since he was captured in August! Samples were collected for disease and pesticide testing, and we are consulting with veterinarians to try to determine the source of mortality for Berg Wind. Without having Berg Wind radio-collared, his body never would have been discovered, and so the radio-collar filled an important task in allowing us to recover Berg Wind's body in sufficient time to learn why he died, and critical threats to caracals in the Cape Peninsula.

MADALA (Caracal #12, TMC12)

Madala, whose name comes from the Nguni languages and respectfully means ‘old man,’ was captured on August 24, 2015 near the Silvermine Area that burned in March. He is one of our oldest caracals caught to date, based on extreme tooth wear and facial scaring, and is estimated to be between 10-13 years of age! He weighed 11.9kg.

Although our ‘old man's’ teeth are but worn to nubs, we've observed him to be a successful hunter still! Through our diet study, we have discovered he sometimes preys on birds and squirrels. As we've seen with other adult males, the area Madala uses is much larger than the areas adult females and juvenile males use. So far, although we predicted he'd travel all the way to Cape Point, so far we've seen him in areas from Constantia all the way to Kommetjie!

HOPE (Caracal #13, TMC13)

Hope was captured on August 26, 2015 in the Silvermine area, just two days after Madala’s capture, in the very same trap site! Weighing 8.5 kg, Hope is one of the larger females we've captured so far. She is a young adult female. Hope’s name was chosen for several reasons. As the 4th female captured in the Urban Caracal Project, we rejoiced at the opportunity to collect more data on what the female caracals are doing in the Peninsula. Further, and most exciting, Hope was pregnant! She would give birth to a litter of kittens soon. Having trapped this reproductive female in a recently burned area showed that not only are these cats surviving in the areas post-fire, but are even able to reproduce in those areas! The presence of reproducing caracals in recently burned areas shows the resilience of wildlife in the face of devastating habitat change, and the recovery for post-burn areas in Cape Town.

In November 2023, Hope’s body was recovered. Hope was a fully grown adult when we first met her in 2015, which means she was 9 or 10 years old when she died. This is incredible for an urban caracal! She was also an excellent mother. While she was collared she had two kittens, so we were able to study caracal reproduction and denning behaviour. She seemed to have kittens yearly, as after her collar dropped off, we received multiple reports of her with babies in tow.

Her body was found near Zwaanswyk in the Upper Tokai section of Table Mountain National Park. She was recognisable by her green ear tags. She had sustained multiple wounds, a broken jaw, and x-rays showed severe internal injuries. Based on the injuries and the tracks around the body, we believe Hope was killed by dogs. In this section of the park, dogs are not allowed. This was a stark reminder of the danger that dogs can pose to wildlife. This incident was the latest of multiple cases of dogs attacking caracals that we have recorded.

Sighting of Hope in the Constantia area of Cape Town in May 2022. She would be 8 or 9 years old here! Photo by Jennifer Louw

AZURE (Caracal #16, TMC16)

Azure is a young adult male captured in Silvermine area on November 10, 2015. He is so named because we noted immediately that his eyes were an amazing blue color! He roams around areas we've also seen Madala, Ratel, and Atticus! Shortly after his capture Azure traveled around the wine lands of Constantia where diet studies revealed that he largely feasts on guinea fowl, Egyptian geese and perhaps rodents.

Azure surprised everyone and made a trek around all of table mountain and into the Lion’s Head area, over 20km north from where he was caught! Like Jasper and Berg Wind, Azure was likely around dispersal age when captured and was looking for his own territory. Discussion of his movements were featured both in an infographic and a blog posting describing his movements compared with another young male outside of Cape Town. His radio collar was on for 185 days with 1800 GPS locations. His collar was successfully recovered on the 13th of May in the Silvermine area.

EBEN (Caracal #17, TMC17)

Eben is a large adult male caught on November 21, 2015 in Wynberg, weighing 12.9kg. Like many of the other adult males, Eben was quite feisty during his capture, and so was named after famed rugby player Eben Etzebeth! But his movements have certainly surprised us. While most of the adult males we have observed have had very expansive areas that they use, while radio-collared, Eben primarily used a vineyard area encompassing only 1 square kilometer! He would occasionally make his way into Table Mountain National Park via a narrow greenbelt through a residential area, but after a few days journey, he always returned to the same small vineyard in Wynberg (west of the M3). Eben's ability to make a home in the middle of a residential area like Wynberg shows us just how adaptive these cats are to urban environments!

By following Eben's movements, we have discovered that he frequently preys on birds such as guinea fowl and Egyptian geese. To make these discoveries, we’ve also learned how thick the vegetation is that he travels through! For a large cat he certainly has no problem making his way through brambles and vines. Overall, Eben has added some very unique data to the study.

TYGER (Caracal #18, TMC18)

Tyger is a young male caracal, probably close to 2 years old, that was the 18h caracal for the Urban Caracal Project, and the 16th that we radio-collared. He's quite an interesting cat! He was hit by a car in the northern suburbs of Cape Town in late 2015. One of his legs was broken, but it seemed that if the leg could heal, he would survive. The Cape of Good Hope SPCA worked to rehabilitated him. He had surgery to fix the broken leg and was carefully monitored and cared for. Within a couple months, Tyger was ready to be released. With the help of a SANParks colleague and permission granted by the SPCA, on December 23, 2015, we radio-collared Tyger. He was then released into the Tygerberg Reserve near the suburbs where he was initially found hit by a car. Because of our limited resources, to collect data on him could be a gamble. Here would be a caracal that had a broken leg that was repaired in captivity– a very stressful environment for a wild animal. If Tyger just hung around the reserve, would that be because his leg wasn't completely healed, or would it reflect his natural behavior? We happened to have a radio-collar that had only half-battery after it was recovered from the body of another caracal, Berg Wind, that died of disease. So if the data were questionable, the use of Berg's half-battery collar would not be too big a loss.

But what a surprise Tyger has proven to be! After only 10 days of laying low in the urban reserve, he was ready to take off! Tyger found a narrow strip of relatively connected habitat and used the corridor to leave the reserve. And then straight north he went all the way to Malmesbury! He made a 55 kilometer trek, suggesting that he was in dispersal mode, looking for an unoccupied territory to call his own. Tyger's story could be one of success. He seems to have settled down in the Malmesbury area where there are agricultural and reserve open spaces that likely provide great hunting ground for him. It is unfortunate that his collar ran out of battery before we established how he would settle in, but the last of his movements spanning approximately 6 weeks suggest he was exploring a potential territory of his own. Unfortunately, his collar reached the end of it's battery life in mid-March, and we able to send a signal remotely, through a web interface, to the radio-collar to fall off.

ZOLA (Caracal #19, TMC19)

Zola was captured on the 13th of January 2016 and after several months of target trapping she was our first Cape Flats caracal capture. She weighed 8.05kg when captured and proved to be the project’s fifth adult female. She was caught in the Rondevlei Nature Reserve just days before Xolani followed her scent into the exact same trap! Zola means “quiet” in Xhosa and seemed to be a fitting name for this calm young lady.

Since she has been collared Zola has yet to leave the safety of the Rondevlei/Zeekovlei area, largely because of the urban development surrounding the reserves on all sides. As a female she is expected to have a relatively small home range but the urbanization of the area is impeding her ability to choose where that home range is established. By travelling to some of her GPS locations for diet investigation studies, the team has found that Zola enjoys some of the thickest bush they’ve seen so far. And who can blame her with hippos running around the reserve! By analyzing her GPS points we hope to compare how she uses her habitat compared to the females in less restricted areas. We also can’t wait to see how she interacts with Xolani!

XOLANI (Caracal #20, TMC20)

Just three days later as we have often seen with the our capture stats, we captured our biggest male yet! Xolani weighed in at a whopping 13.5 kg when he was caught on the 16th of January 2016 in Rondevlei Nature Reserve. As can be expected from such a large male, he was a bit of a handful when he was captured. Ironically enough we still named him Xolani, meaning “peace” in Zulu, to go along with his fellow Rondevlei caracal Zola.

Both Zola and Xolani were captured with hopes of assessing their movements in and around the cape flats, an extremely densely populated region on the east side of the city. In the short time that Xolani’s collar has been transmitting data we have seen that he consistently resides in Rondevlei, but has made some trips into the neighboring township of Philippi. Such a large caracal would theoretically have a substantial home range in a more natural environment but Xolani (along with Zola) is clearly hindered by the Cape Flats developments surrounding the reserve. Hopefully Xolani’s future data will illustrate more extensive wildlife movement through the city and present us with possible solutions to habitat isolation.

STRANDLOPPER (Caracal #21, TMC21) and SPITFIRE (Caracal #22, TMC22)

On the 18th of January the Urban Caracal Project was pleased to find that we had captured not one, but two sub-adults caracals near the Noordhoek wetlands! They were caught about 200 meters from each other. Strandlopper (meaning “beach walker” in Afrikaans) and Spitfire (named so for her feisty and tenacious spirit) were both safely and humanely fitted with GPS radio-collars. Based on weight, tooth wear, age, proximity, and that they traveled together for a time, they are presumed siblings.

As a first for the Urban Caracal project we will have the opportunity to study the diet and habitat preferences of our first juvenile female, Spitfire!

SCARLETT (Caracal #23, TMC23)

Photo of Scarlett at the time of her capture. Credit: Dr. Laurel Serieys

Scarlett was an extremely exciting capture for us…she was the first GPS-collared (February 11, 2016) in Cape Point Nature Reserve (Cape of Good Hope), weighing 7.6 kg. She was clearly on older caracal- her teeth were worn and she had scars to boot. As can be expected with an older female she also showed signs of previous reproduction.

While very little was known about caracals in Cape Point, Scarlett was the first of 5 Cape Point caracals we monitored that helped us compare data between Cape Point and the rest of the peninsula to paint a meaningful picture regarding the effects of urbanization on caracals.

Unfortunately, Scarlett’s time on the project was short. She died approximately 3 weeks after collared from unknown causes. By time we found her body, she was extremely decomposed with only skin and bones remaining. We performed an autopsy and found only 1 broken rib, so it’s very hard to know what happened. It’s perhaps most likely she was injured in a fight with another caracal, but it’s also possible she was hit by a car or perhaps kicked by the large antelope or zebras in the reserve. After she died, we were able to determine she was 10 years old, making her the oldest caracal in the Peninsula that we were able to accurately age (it requires sending a tooth to a lab, so we only do the procedure after a caracal has died).

PROTEA (Caracal #24, TMC24)

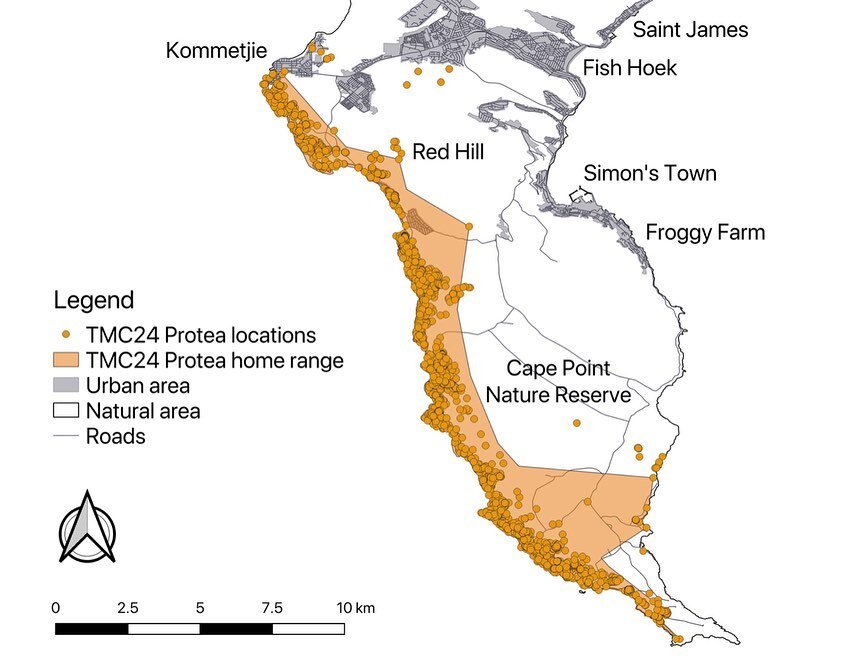

The team was unsure of how many caracals were using the Cape Point Reserve, and even more unsure about trapping success in such wide open areas. Luckily just one week after Scarlett’s capture another caracal found her way into one of the traps! Protea was humanely captured and radio collared on the 18th of February and weighed 7.15kg. During the capture it became clear that Protea was a very healthy and beautiful young female. She had a fantastic coat and was even photogenic while pictures were being taken! Judging by her nipples Protea had yet to give birth, and was estimated to only be about 2 years old.

Protea was GPS-collared twice, and so we had the opportunity to learn more than we typically do about these caracals’ movements. Her movements in particular were extremely interesting, and taught us a lot about how caracals in the southern Peninsula may differ in diet and movements compared to caracals in the northern Peninsula. At 48 sq.km., her home range is the largest we documented for any female. But what’s most interesting is that she hardly left the coastline, moving up and down the coast from Cape Point to Kommetjie. She favors sea birds, often hunting cormorants and sea gulls. Even more interesting is the fact that Protea occasionally made her way out of the park and all the way north to the edge of Kommetjie! While this is not quite as daring of an adventure as some of the more urban caracals, it shows us that even cats located in the most protected reserves will also occasionally access areas populated by humans. We are unsure what her fate is as after her second collar fell off, we have no further data collected for her. Hopefully she’s still out there enjoyed the beach lifestyle!

TITAN (Caracal #25, TMC25)

Titan is our third cat, but first male, humanely captured in Cape Point. After waiting patiently for two weeks since the capture of the last cat in Cape Point, Protea, we captured Titan on March 2, 2016. His name derives from the Titans of Greek mythology and was chosen because of his “titanic” size. At 16 kg, he is by far the largest cat we have captured to date. Based on his excellent body condition and size, we estimate that he is a male in the prime of his life. We are very excited to compare the movements and diet of such a large male to those of smaller caracals both inside and outside of Cape Point. Because the resources and habitat available to these predators are quite different inside the park when compared to the more urban areas explored by previously collared caracals, we hoped Titan would yield some exciting and unique data. He definitely lived up to that expectation by utilizing a massive home range, including areas within the park but also venturing outside as far away as Simon’s Town!

PROSPERO (Caracal #26, TMC26)

We first met Prospero in the middle of the night in May 2016, after receiving a call from a concerned resident reporting a caracal trapped in an illegal gin trap on a neighbor’s property. We dashed to the Hout Bay property and were met there by project vet Aimmee Knight (Penzance Veterinary Clinic). We found Prospero completely exhausted after fighting to get out of the trap. We sedated him and took him for x-rays. Luckily, he only had three dislocated toes which were easily reset. Otherwise, he was a big, healthy 12 kg boy. After resting at the SPCA for a few days, we GPS-collared him and released him back in Table Mountain National Park.

Prospero was the first caracal to draw our attention to the issue of poaching within the City of Cape Town. The illegal gin trap that caught him was set to protect a rabbit shed, which were food for the property gardener. Those who set poacher’s traps are often hungry, less-fortunate community members, who are trying to protect a food source, or are trying to find food (bushmeat).

As a young male, he travelled far in search of a territory to call his own. In the 6 weeks he was collared, he used areas between Rhodes Memorial to Cape Point - 50 km as the crow flies! But his genetic data tell us that he was born outside of the Peninsula, likely from the Cape Flats region! After visiting Cape Point, Prospero travelled back to Hout Bay where he was hit by a car. We learned then that he was only 2 years old and was exposed to rat poisons. Prospero’s story teaches us about the gauntlet of threats that a single urban caracal can face.

While some may question why we released him back where we found him, the answer is simple. Numerous scientific studies tell us that relocating wild cats, especially ones with large territories, is (in nearly all cases) a death sentence. Prospero had the best chance of survival in an area he was already familiar with. For this reason (and many others), relocation beyond the bounds of an animal’s home range is not permitted by CapeNature. Importantly, the threats we’ve learned about in Cape Town are not limited to Cape Town. Cars, habitat loss, poisons, and poachers are widespread across the Western Cape. To help all wildlife in Table Mountain, we urge people to not use rat poisons, to drive slowly on roads that abut green space, and protect domestic animals by building “predator-proof” enclosures, or bringing pets indoors, especially at night.Prospero was collared on the 17th of May. Prospero's name was chosen because we felt that his story resonated with that of Prospero in Shakespeare's the Tempest. The name also means "fortune" or "luck."

To read more about his story and how he was caught in a gin trap, click here.

Disa (Caracal #27, TMC27)

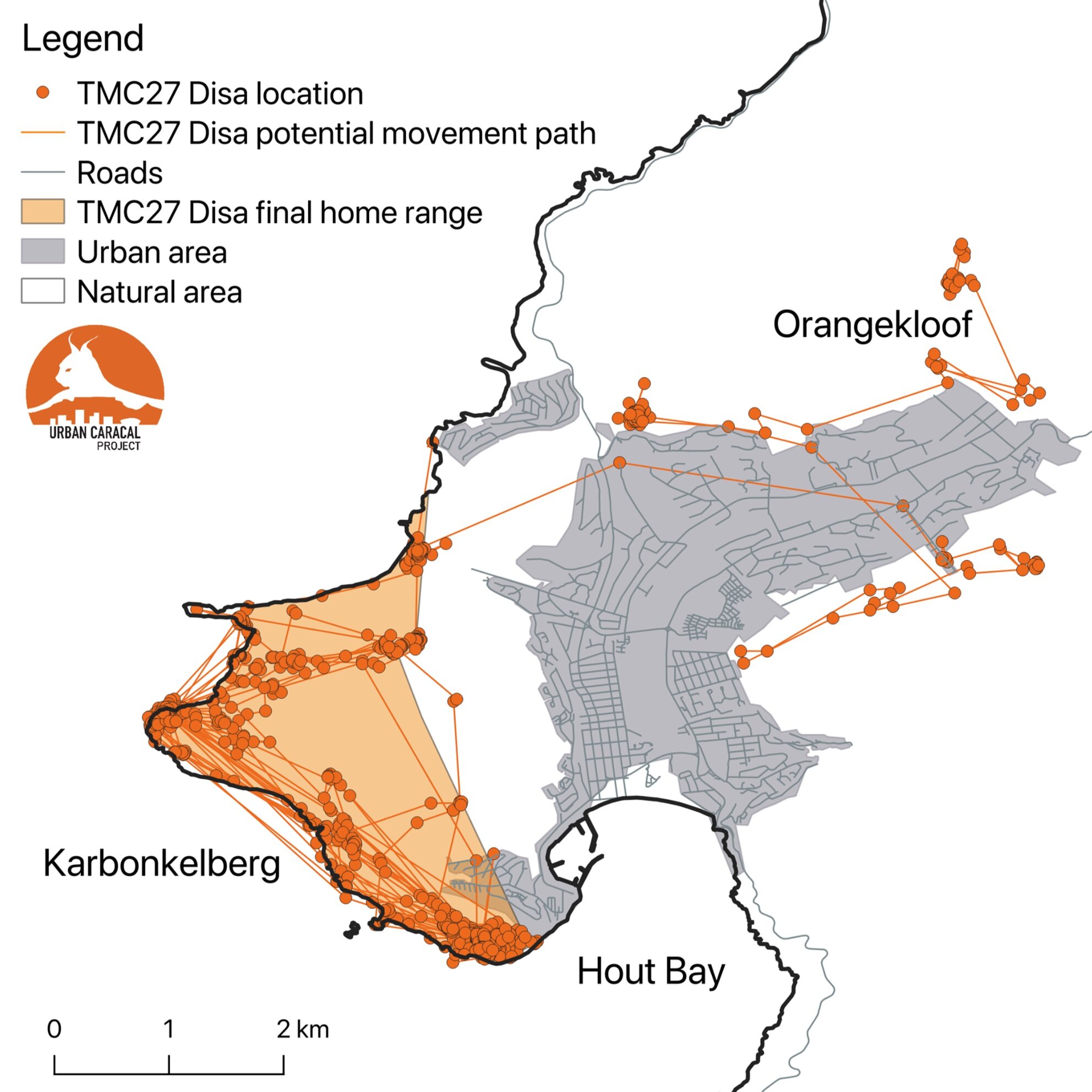

We first met Disa when the coastal section of the City of Cape Town asked us to assist with an acute intervention to address a caracal killing penguins at Boulders. While we don’t support relocations as a solution for conflict, we agreed to a one-off relocation as a short-term solution while longer term strategies could be developed. When we caught a caracal adjacent to Boulders beach, we were surprised to discover it was a mature female rather than the subadult male we thought most likely to predate on penguins at the colony.

Suspecting she may be supporting offspring, we recommended relocating her within her likely home-range, but we were instructed to relocate her to Orangekloof, Hout Bay despite the fact that all of our data collected to that point indicated that Orangekloof was too far to be within her home range. For 23 days she explored her new Hout Bay surroundings before settling in the Karbonkelberg area, where she stayed until her collar automatically dropped off in November 2016. At her capture we found her canine teeth were both damaged. This didn’t seem to slow her down —she successfully hunted Cape cormorants and dassies. She also regularly traversed the steep cliff faces around the Karbonkelberg peak, and we even had to source assistance from rock climbers to retrieve her collar!

Despite being released into a more urbanised area, Disa continued to behave more like a ‘rural’ southern Peninsula caracal. She avoided urban areas, preferred hunting on the coast and continued hunting mainly seabirds. This reinforces what is known for other species – individuals that are moved from their territories are more likely to succeed in areas that resemble “home.”

Disa’s relocation reinforced for us why relocation is an inadequate management strategy. Disa survived her relocation, but so did the problem of caracals preying on penguins. It turns out that Disa had a male offspring who was left abandoned in the colony and turned to the easy food source of penguins. Stay tuned for his story. Managing predators around a land-based penguin colony is a complex problem but because the penguin colony is small (less than 1 sq.km), in order to protect both penguins and caracal, our recommendation is to build strategic fencing based on access points from the mountain to the colony.

Luna (Caracal #28, TMC28)

Luna, captured in July 2016, was the third adult female we captured in Cape Point. We were super excited to monitor her because after anaesthetizing her (with the assistance of a vet), we discovered she was pregnant! Swipe to see photos of her baby bump. We have observed that caracals on the Cape Peninsula usually have kittens between October – December, and their gestation period is approximately 78 days. Perhaps because she was raising young, we never observed Luna to use urban areas. She had a fairly small home range of 16 sq.km (see map), but denning female home ranges always shrink for wild cats.

We were able to monitor her while she was denning, and we were hopeful to visit her den site (following scientifically-standardized and ethically approved protocols) to learn more about caracal reproduction and development. Although we tried to visit her den a couple of times, she was extremely skittish and moved the den site if we attempted to investigate, or even put up cameras nearby (see video of her carrying her kitten to a new den site). She clearly was a very excellent, doting mom. We initially thought she was so skittish because of the baboons in the area. However, we now think that these Cape Point caracals are just less comfortable with human disturbances. While there isn’t a huge amount of information available on caracal reproduction in the wild, with our limited observations, it seems that kittens exclusively stay in and around the den site until around 4-6 weeks of age, at which point they will start to move around with mom to learn the life of a caracal! Luna’s collar dropped off automatically and was retrieved in December 2016 so we were unable to continue monitoring her after that.

Luna, suspicious of our cameras, is seen here moving her kitten to a new den site. On the left she spends significant time sniffing the camera, and an hour later moves her (big) baby!

Orion (Caracal #29, TMC29)

Orion was collared on August 1. Barely a month later, his body was recovered. At his capture, he was an adult male, weighing in at a healthy 12.2 kg. We think Orion’s likely cause of death was exposure to pesticides and disease. Our testing shows he was exposed to anticoagulant rat poisons, as well as DDT and PCBs, and evidence of blood parasites, while tests for other common feline diseases are still pending.

Beskuitjie (Caracal #30, TMC30)

We first met this caracal after she wandered into someone’s house in Durbanville (near Tygerberg Reserve). As a young female approximately 1 year old, she was clearly confused when she stumbled into someone’s home, but stayed there hiding in a kitchen. While it may sound unbelievable that a caracal wandered inside someone’s house seemingly very confused, it’s actually not super uncommon for young wild cats to get “lost” in urban areas. As young individuals looking to “move out on their own,” they sometimes catch themselves in very awkward situations! Typically, they are wandering around learning about their environment, and where is safe, and unsafe, to be, and before they know it, someone has spotted them or the sun has come up! Their response, like most other cats, is just to hunker down and hope that no one notices them!

By time we met Beskuitjie, we had completed our GPS-collaring work and so we only ear-tagged her before she was released back into Tygerberg Reserve with the hope she would find a place to call her own territory.

We next met Beskuitjie in September 2018 after receiving a call from Cape Nature about a tagged female caracal that was hit by a car near Paarl, approximately 50 km east of Tygerberg! Not only that, she was pregnant, and we found two fetuses in her uterus. This young female taught us that young caracals need a lot of space, and she is the second caracal in the northern suburbs that dispersed approximately 50 km before setting up her own territory someplace new.

Beskuitjie’s story highlights how resilient these wild cats are in the face of rapid urbanisation but also some of the many threats they must face, and that when a car kills a reproductive female caracal, sometimes there’s a disproportionate impact on the population. With ongoing fragmentation of natural habitat by buildings and roads, it is vital that we attempt to maintain connected green space within and adjacent to cities to conserve urban wildlife.